Very pleased to to announce that the GlobalSurg protocol has just been published in BMJ Open. As well as this, the study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov on the 29 June 2014. Both of these are important to ensure transparency and that the protocol doesn’t change after the start of data commencement.

Investigator contact details should continue to be available after completion of clinical trials

Why oh why does the National Library for Medicine remove investigator contact details from clinicaltrials.gov after completion of a trial. We need to contact them to ask why their trial is not published!

BMJ letter from us on the subject:

For successful translation of results from research into practice there must also be timely dissemination of research findings (1). The Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act requires trials that are subject to mandatory reporting to post results within 12 months of study completion on ClinicalTrials.gov (2). Despite this initiative, less than a quarter of trial investigators comply (3).

Maruani and colleagues report that email reminders of the legal requirement to post results significantly improve reporting at six months (4). Any intervention that increases dissemination of clinical trial results is welcome and the authors should be commended for their efforts.

However, we do not understand the authors’ described methods. They report that the cohort included trials “that had available contact details (email addresses) of responsible parties”, and go on to state that they “extracted the email addresses of responsible parties from ClinicalTrials.gov”. In the discussion they highlight “the need for updating email addresses of responsible parties in ClinicalTrials.gov”.

We would be interested to know how this is possible as all email addresses for completed trials are removed from ClinicalTrials.gov as a matter of policy by the National Library of Medicine (Table 1).

We asked the National Library of Medicine (NLM) to comment on this. In addition, we asked what advice they would give a patient who had taken part in a completed clinical trial, and wished to contact the investigators to enquire about trial results. They responded:

“If the record is closed or completed, we remove all contact information in the location and contact section since there is no reason why a potential patient would need to contact them.”The NLM will not provide contact email addresses on request, despite these previously being available on ClinicalTrials.gov while the trial was recruiting.

The removal of previously published contact information from ClinicalTrials.gov has important implications for transparency in trial reporting. Interventions, such as that proposed by Maruani, cannot be delivered at scale while this practice exists. Searching for contact details manually with Google or Pubmed is difficult at best and impossible for many, who may include patients that have participated in a study and wish to contact the investigators about trial results.

References

1. Ross JS, Tse T, Zarin DA, Xu H, Zhou L, Krumholz HM. Publication of NIH funded trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional analysis. Bmj 2012;344: d7292.

2. Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, Califf RM, Ide NC. The ClinicalTrials.gov results database–update and key issues. N Engl J Med 2011;364(9): 852-860.

3. Prayle AP, Hurley MN, Smyth AR. Compliance with mandatory reporting of clinical trial results on ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional study. Bmj 2012;344: d7373.

4. Maruani A, Boutron I, Baron G, Ravaud P. Impact of sending email reminders of the legal requirement for posting results on ClinicalTrials.gov: cohort embedded pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Bmj 2014;349: g5579.

Adverse outcomes demand clear justification when introducing new surgical procedure

The introduction of new surgical procedures is fraught with difficulty. Determining that a procedure is safe to perform while surgeons are still learning how to do it has obvious problems. Comparing a new procedure to existing treatments requires the surgery to be performed on a scale rarely available at early stages of development. The IDEAL framework helps greatly with this process.

When performing liver surgery, it is crucial that sufficient liver is left behind at the end of the operation to do the necessary job of the liver. This is particularly important in the first days and weeks following surgery. When disease demands that a large proportion of the liver is removed, manoeuvres can be performed before surgery to increase the size of the liver left behind. The disease is invariably cancer and the manoeuvres usually involves blocking the vein supplying the part of the liver to be removed, a procedure called portal vein embolisation. This causes the liver to think part of it has already been removed. The part which will stay behind after surgery increases in size, hopefully sufficient to do the job of the liver after surgery. This often works but does require a delay in definitive surgery and in some patients does not work sufficiently well.

An alternative procedure has come to the fore recently. The ALPPS procedure (Associating Liver Partition and Portal vein Ligation for Staged Liver resection) combines this embolisation procedure with an operation to cut the liver along the line required to remove the diseased portion. But after making the cut, the operation is stopped and the patient woken up. Over the course of the following week the liver being left behind increases in size – quicker and more effectively say proponents of the ALPPS procedure. After a week, the patient is taken back to the operating room and the disease liver portion removed.

So should we start using the procedure to treat cancer which is widely spread in the liver?

The difficulty is knowing whether the new procedure is safe and effective. Early results suggest quite a high mortality associated with the procedure. But of course for patients with untreated cancer in the liver who do not have surgery, the mortality rate is high.

A study has been published which contains some positive data: ALPPS offers a better chance of complete resection in patients with primarily unresectable liver tumors compared with conventional-staged hepatectomies: results of a multicenter analysis.

However, it is still my feeling that the results of the procedure are not good and the traditional portal vein embolisation procedure seems to work well in our patients. Here is our letter with our concerns in response.

We read with interest the multicenter study by Schadde and colleagues in the April issue regarding the novel procedure of Associating Liver Partition and Portal vein Ligation for Staged Liver resection (ALPPS) [1]. Since the initial description 2 years ago [2] ALPPS has gained popularity as a surgical option for treating patients with advanced liver lesions not considered amenable to conventional two-stage or future liver remnant-enhancing procedures propagated by Rene Adam et al. [3] a decade ago. Indeed, the explosion of interest in ALPPS by surgeons and its adoption as a procedure of choice is concerning, given that the procedure appears to come with considerable cost to the patient, as shown in this study. The increased severe morbidity of 27 versus 15 % and the mortality of 15 versus 6 % may not achieve traditional measures of statistical significance in this study, but the effect size is concerning, and the direction of effect is consistent across outcome measures and studies. Is ALPPS in its current form safe enough for the widespread adoption that has occurred given increasingly effective nonsurgical approaches, including ablation, chemotherapy, selective internal radiation therapy [4], and growth factor/receptor inhibition?

As the authors rightly point out, the risk of selection bias is significant given the study design. It is unclear whether the logistic regression analysis adequately adjusts for the imbalance in baseline risk in favor of the ALPPS group: why, for instance, was operative risk (ASA grade) not controlled for in the multivariate analysis?

One of the potential benefits of a two-stage procedure is that it may disclose biologically unfavorable disease. By its very nature, ALPPS does not lend itself to such selection given the short time interval between the first and second stages. The authors appear to reject this argument, citing a similar overall recurrence rate seen in this study. We were puzzled with this position given that the study highlights an interesting observation: in the PVE/PVL group 11 % of patients had systemic progression prior to the second stage. Presumably this group of patients would not have benefitted from ALPPS.

In our practice, patients who may be deemed by others to be ideal candidates for ALPPS are seldom not amenable to either a two-stage liver resection or a single-stage resection with prior volume-enhancing maneuvers. Indeed, it is difficult to understand why an ALPPS approach was used at all in some of the cases presented at recent international conferences. We wonder what proportion and kind of patients with advanced liver lesions would really benefit from the ALPPS approach. The international ALPPS registry will perhaps provide clearer evidence for the role of this challenging approach to liver resection.

1. Schadde E, Ardiles V, Slankamenac K et al (2014) ALPPS offers a better chance of complete resection in patients with primarily unresectable liver tumors compared with conventional-staged hepatectomies: results of a multicenter analysis. World J Surg 38:1510–1519. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2513-3

2. Schnitzbauer AA, Lang SA, Goessmann H et al (2012) Right portal vein ligation combined with in situ splitting induces rapid left lateral liver lobe hypertrophy enabling 2-staged extended right hepatic resection in small-for-size settings. Ann Surg 255:405–414

3. Adam R, Delvart V, Pascal G et al (2004) Rescue surgery for unresectable colorectal liver metastases downstaged by chemotherapy: a model to predict long-term survival. Ann Surg 240:644–657 discussion 657–658

4. Gulec SA, Pennington K, Wheeler J et al (2013) Yttrium-90 microsphere-selective internal radiation therapy with chemotherapy (chemo-SIRT) for colorectal cancer liver metastases: an in vivo double-arm-controlled phase II trial. Am J Clin Oncol 36:455–460

[gview file=”http://www.datasurg.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Rohatgi-et-al.-2014-ALPPS-Adverse-Outcomes-Demand-Clear-Justification.pdf”]

GlobalSurg recruitment starting soon

I’m excited to be involved in an enthusiastic young collaborative called GlobalSurg. Research in surgery has been a predominately first world affair and it is absolutely essential to see international collaboration including developing nations. Our study focusses on emergency abdominal surgery and complements a similar initiative looking at elective abdominal surgery, ISOS.

Why this study and why now? Surgery has been referred to as the neglected step child of global public health, a sentiment I completely agree with. Diseases effectively treated with surgery are becoming the public health priority for developing nations, a fact highlighted by the excellent International Collaboration for Essential Surgery (ICES) and important Right to Heal campaign.

Least wealthy countries account for 35% of the global population yet undertook only 3.5% of all surgical procedures in 2004.

This GlobalSurg project aims to be the first of many. It will establish what happens to patients across the world after emergency abdominal surgery

The primary outcome measure here is pragmatic: which patients are still alive 24 h following emergency surgery? A number of secondary measures will provide depth. Case mix will be determined as far as is possible and an analysis of facilities included.

Anyone can still get involved in GlobalSurg and I would encourage you to do so. We have everyone from professors of surgery in large first-world urban centres to small community hospitals in developing countries.

It only requires data collection over any two week period in July-November 2014. Patients are easy to identify and there are only 30 patient related data-points to collect. Data can be collected on paper or directly into our REDCap system, which I will write more about in the future.

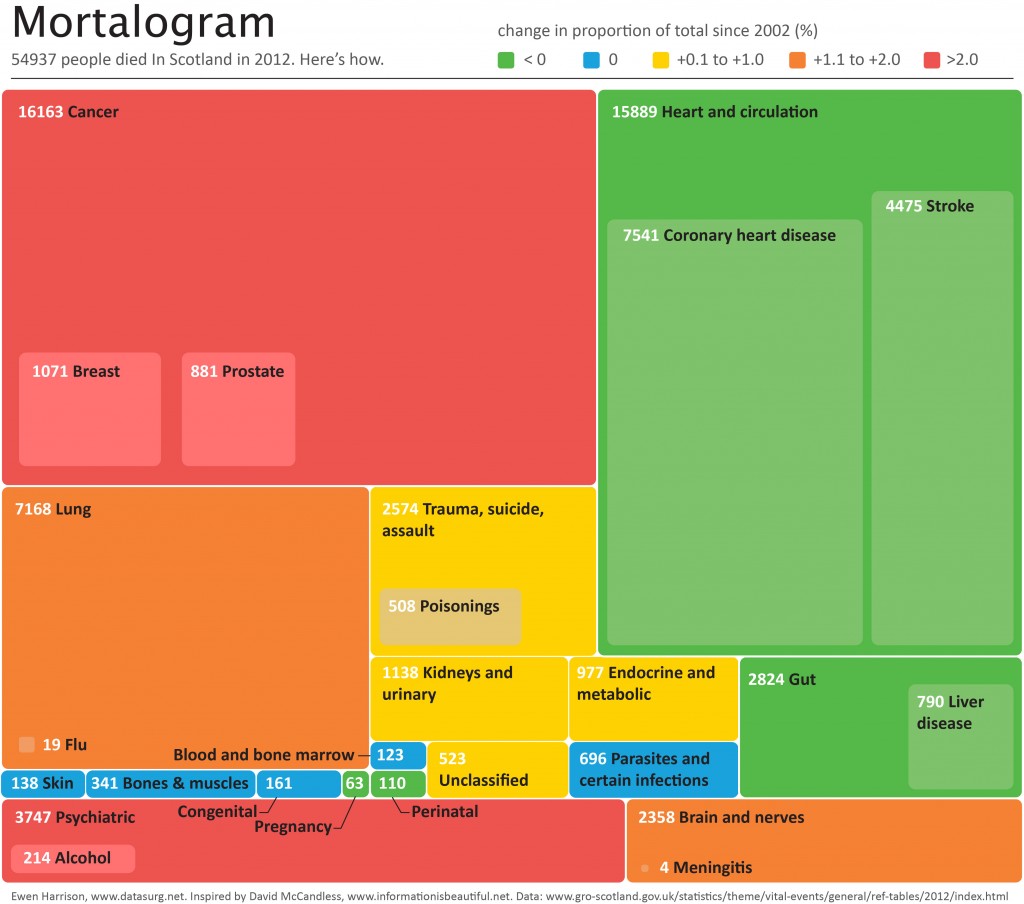

Mortalogram

Life expectancy of acute hospital inpatients

I liked the study published this week by David Clark and Christopher Isles.

On 31st March 2010 there were 10,743 inpatients in 25 Scottish teaching and general hospitals.

One year later 3098 (29%) were dead.

That sounds a lot and is a lot. As the authors point out, the study is biased to long term inpatients as it is a prevalent sample (those in hospital) rather than an incident sample (those admitted to hospital). The latter would be more informative to us in surgery.

Another important observation: of those that died, 32% did so during the index admission.

Our acute hospitals are not set up to be good places to die. They could and should be better.

The focus of care may too often be cure, doctors treating illnesses rather than patients. We are fortunate to have excellent palliative care services within our hospital, but the recent media outrage on the Liverpool Care Pathway has left many clinicians uncertain when looking after patients at the end of life. There is no lack of compassion, but a definite of education. This must improve if care is to get better.

Finally, the study reports in the abstract and throughout that men were more likely to die than women. It is unusual that neither the authors, reviewers nor editors picked up that this statement is based on a non-significant result, odds ratio: 1.18, 95% confidence interval: 0.95–1.47. There is no gender effect in the final model.

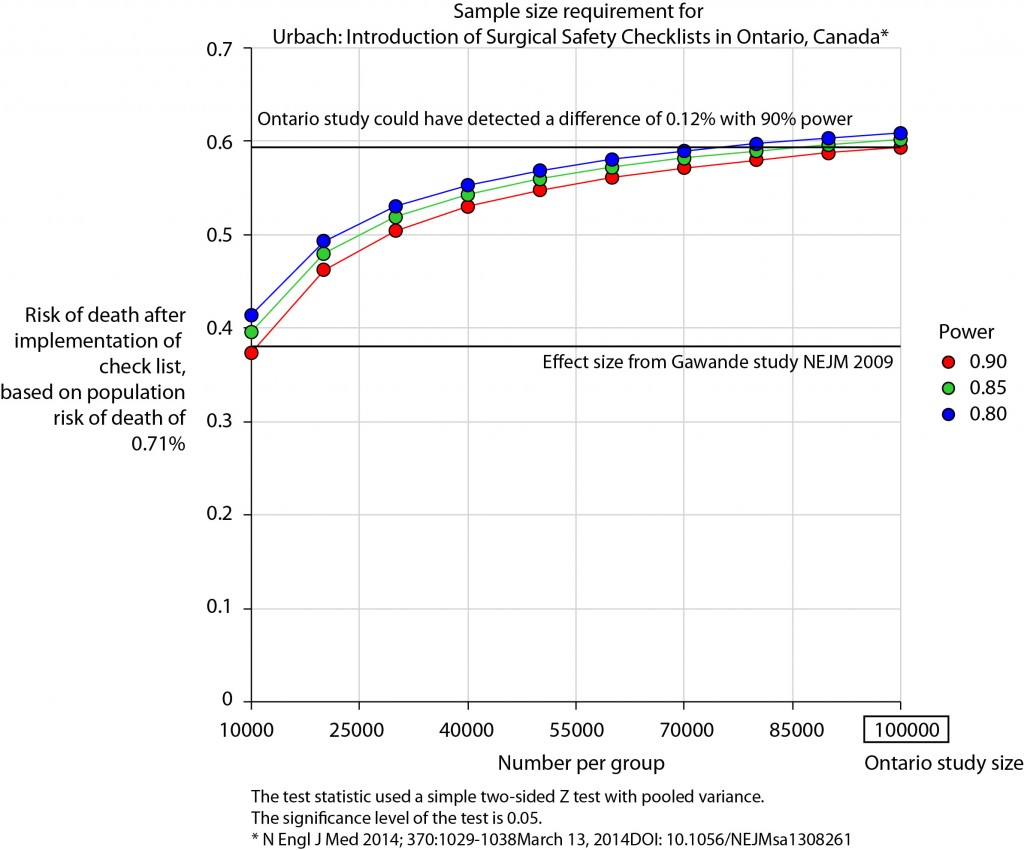

Introduction of Surgical Safety Checklists in Ontario, Canada – don’t blame the study size

The recent publication of the Ontario experience in the introduction of Surgical Safety Checklists has caused a bit of a stooshie.

Checklists have consistently been shown to be associated with a reduction in death and complications following surgery. Since the publication of Atul Gawande’s seminal paper in 2009, checklists have been successfully introduced in a number of countries including Scotland. David Urbach and Nancy Baxter’s New England Journal of Medicine publication stands apart: the checklist made no difference.

Atul Gawande himself responded quickly asking two important questions. Firstly, were there sufficient patients included in the study to show a difference? Secondly, was the implementation robust and was the programme in place for long enough to expect a difference be seen.

He and others have reported the power of the study to be low – about 40% – meaning that were the study to be repeated multiple times and a true difference in mortality actually did exist, the chance of detecting it would be 40%. But power calculations performed after the event (post hoc) are completely meaningless – when no effect is seen in a study, the power is low by definition (mathsy explanation here).

There is no protocol provided with the Ontario study, so it is not clear if an estimate of the required sample size had been performed. Were it done, it may have gone something like this.

The risk of death in the Ontario population is 0.71%. This could have been determined from the same administrative dataset that the study used. Say we expect a similar reduction in death following checklist introduction as Gawande showed in 2009, 1.5% to 0.8%. For the Ontario population, this would be equivalent to an expected risk of death of 0.38%. This may or may not be reasonable. It is not clear that the “checklist effect” is the same across patients or procedures of different risks. Accepting this assumption for now, the study would have only required around 8000 patients per group to show a significant difference. The study actually included over 100000 patients per group. In fact, it was powered to show very small differences in the risk of death – a reduction of around 0.1% would probably have been detected.

Similar conclusions can be drawn for complication rate. Gawande showed a reduction from 11% to 7%, equivalent in Ontario to a reduction from 3.86% to 2.46%. The Ontario study was likely to show a reduction to 3.59% (at 90% power).

The explanation for the failure to show a difference does not lie in the numbers.

So assuming then that checklists do work, this negative result stems either from a failure of implementation – checklists were not being used or not being used properly – or a difference in the effect of checklists in this population. The former seems most likely. The authors report that …

… available data did not permit us to determine whether a checklist was used in a particular procedure, and we were unable to measure compliance with checklists at monthly intervals in our analysis. However, reported compliance with checklists is extraordinarily high …

Quality improvement interventions need sufficient time for introduction. In this study, only a minimum of 3 months was allowed which seems crazily short. Teams need to want to do it. In my own hospital there was a lot of grumbling (including from me) before acceptance. When I worked in the Netherlands, SURPASS was introduced. In this particular hospital it was delivered via the electronic patient record. A succession of electronic “baton passes” meant that a patient could not get to the operating theatre without a comprehensive series of checklists being completed. I like this use of technology to deliver safety. With robust implementation, training, and acceptance by staff, maybe the benefits of checklists will also be seen in Ontario.

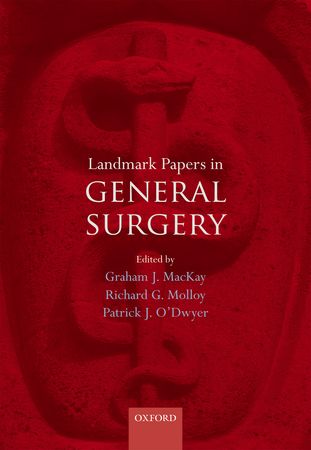

Landmark Papers in General Surgery: Review

A longer version of my review in Surgeons’ News.

When should a clinical study be considered a landmark? Must it have changed practice? Does the strength of the study have a bearing – should only randomised clinical trials be considered, for instance? The new Landmark Papers series from Oxford University Press has volumes in Neurosurgery, Cardiovascular Medicine and Nephrology. A book covering General Surgery from authors based mainly in Glasgow is hot off the press.

The editors have done a great job in producing a clean, well-structured, easy to read book that will be of use to both practising surgeons and trainees. The book is divided by general surgery subspecialty with each chapter containing a number of themes. In emergency surgery, for instance, sections include CT assessment of the acute abdomen and laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy. An important study addressing the theme is provided, sometimes together with related references. Following a brief description, study design and results are tabulated, after which conclusions and a critique are made.

Before opening the book I wondered whether there may be a problem in its conception: in the modern world of the systematic review and meta-analysis, what is the place of a book in which surgeons highlight a single publication in a deliberately unsystematic manner? Is this not harking back to the days when one cites evidence fitting ones prejudices, ignoring troublesome contradictory reports?

Actually, rather than a problem, I found this refreshing. This analysis of individual trials in a detailed manner is reminiscent of the journal clubs we struggle to maintain in our busy modern practice. Despite being an advocate for the systematic review, too often the focus is on the certainty surrounding a point estimate of outcome. This book highlights the importance of clear consideration of the intention of a trial, whether those aims were achieved, what biases exist and ultimately whether the results apply to my patients or not. In any case, in areas where conflict exists, multiple trials are often described and the balance of interpretation discussed in the critique.

Actually, rather than a problem, I found this refreshing. This analysis of individual trials in a detailed manner is reminiscent of the journal clubs we struggle to maintain in our busy modern practice. Despite being an advocate for the systematic review, too often the focus is on the certainty surrounding a point estimate of outcome. This book highlights the importance of clear consideration of the intention of a trial, whether those aims were achieved, what biases exist and ultimately whether the results apply to my patients or not. In any case, in areas where conflict exists, multiple trials are often described and the balance of interpretation discussed in the critique.

Another concern was that it would date almost as soon as it was published. With 140 000 citations being returned from the Pubmed database for an all-fields search for “surgery” in 2012, how can a static publication like this hope to remain relevant? Again, on the whole this concern was unfounded. A condensation of the evidence for surgery, such as this, shows that the pace of change is slower than we possibly recognise. While the majority of included trials are from the last 15 years, there are fewer than I expected from, say, the last 4 years.

A publication such as this puts itself up there to be criticised for the omission of studies deemed important by a reviewer, and it would be remiss of me not to comply. Actually, the editors have done a good job and irritatingly I found it difficult to identify big omissions. On pulling up the top 50 most cited papers in surgery, I found the great majority had been included. In my own (small field), the landmark paper by Mazzaferro on the surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma has been cited more than most other surgical papers (2400 times) and warrants inclusion. The classification of surgical complications by Dindo and Clavien is at number 11 in my top 50 and probably deserves mention.

The editors have achieved their aim with this book and I would recommend it unreservedly. Minor niggles are the truncated “et al” citations – give us the whole citation so we can see the senior author please. No graphs are included which is fine, but where the main study is a meta-analysis, including the forest plot for the primary outcome measure conveys information better than a table. Finally, is there a digital version of this book? I circled the Oxford website in vein but could not find a page where it is possible to buy one.

Must a landmark paper have changed practice? No, as illustrated by the neat discussion on the GALA (general versus local anaesthetic in carotid endarterectomy) trial – an example of a landmark randomised trial that has not changed practice. Must a landmark paper be an RCT? No, as the classic level 4 evidence for total mesorectal excision by Bill Heald demonstrates – some observational studies have done more to alter practice in surgery than many RCTs.

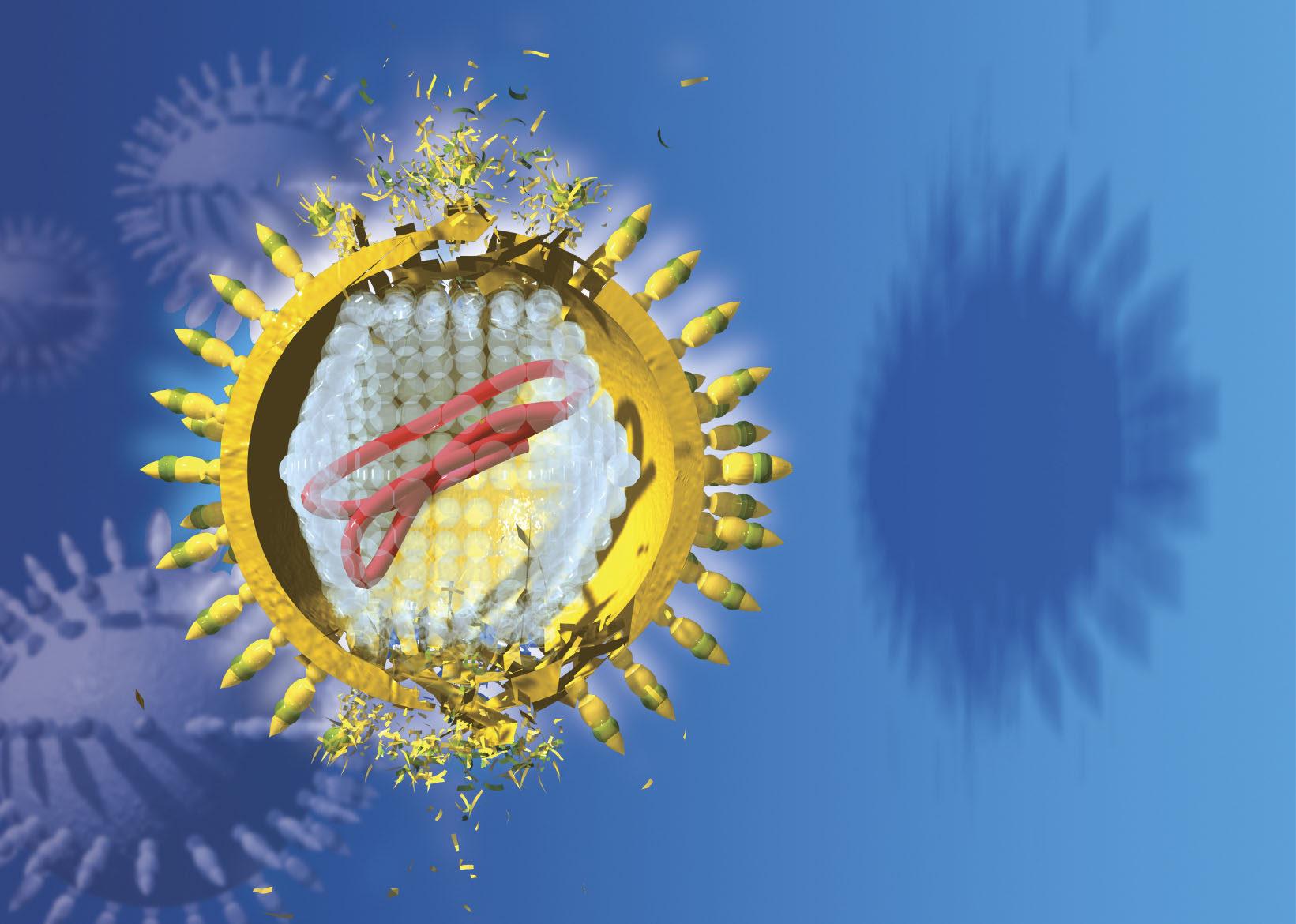

Hepatitis C virus, tumour and liver transplantation

From my HPB highlights this month.

Do patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) on a background of hepatitis C virus (HCV) have worse outcomes after liver transplantation than non-HCV patients? This relatively straightforward question continues to vex and published studies are contradictory. Molecular features of HCC which are associated with aggressive behaviour are up-regulated in the presence of HCV, providing a biological mechanism to support the hypothesis. The theory is borne out in early single centre studies, but the largest published analysis using the United Network for Organ Sharing database published by Thuluvath in 2009 contradicted these. HCV+ patients were shown to have a lower survival rate than HCV- patients, regardless of their HCC status. This is to be expected. However, HCV had no additional negative impact on survival in patients with HCC

In this edition of HPB, Dumitra and colleagues describe a further single-centre study from Montreal. They conclude that HCC+/HCV+ patients have a significantly worse outcome than those with HCC or HCV alone. So why the contradiction? It may be that length of follow-up is important. This study provides survival curves out to 10 years. A cluster of deaths after 5 years in the HCV+/HCC+ group results in a significantly worse outcome in this group, although the number-at-risk are low. However, loss to follow-up is an unusually low 1.2% and explant pathology is available for almost all patients – detail not often available in studies using administrative databases. In a multivariable analysis controlling for recipient age, gender, MELD score and donor risk index (DRI), the combined effect of HCC+/HCV+ gives a hazard twice that of HCC+/HCV-.

HCV graft infection after liver transplantation is universal and the course of recurrent cirrhosis accelerated. Controlling HCV recurrence with newer antiviral agents will improve long-term survival and this study suggests the possibility of additional benefits in HCC+/HCV+ patients. Other modifiable variables such as donor age and DRI are unlikely to have an impact, given HCC patients rarely have the luxury of a wide choice of donor grafts.

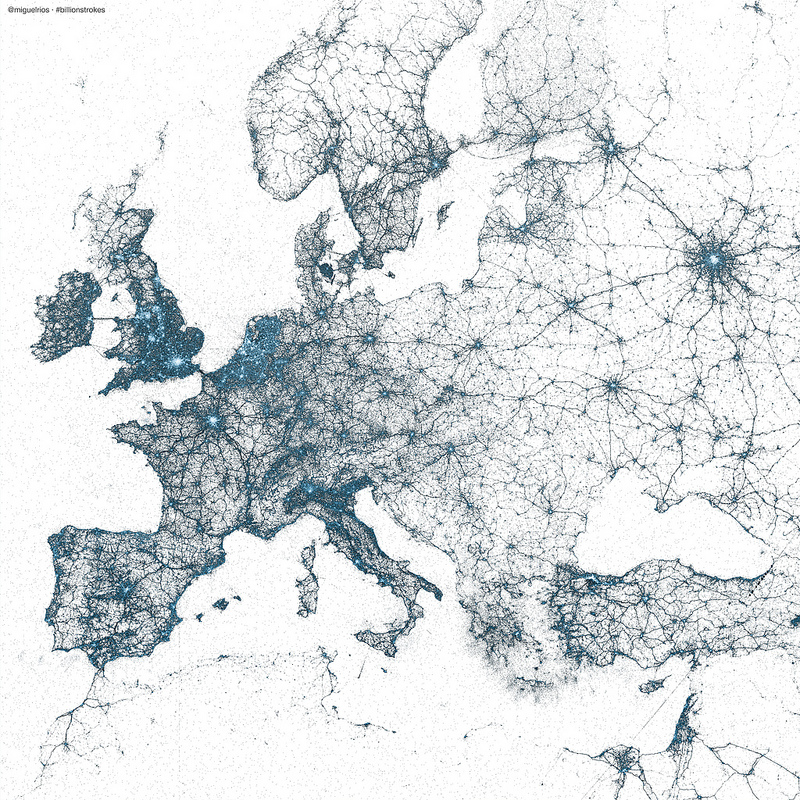

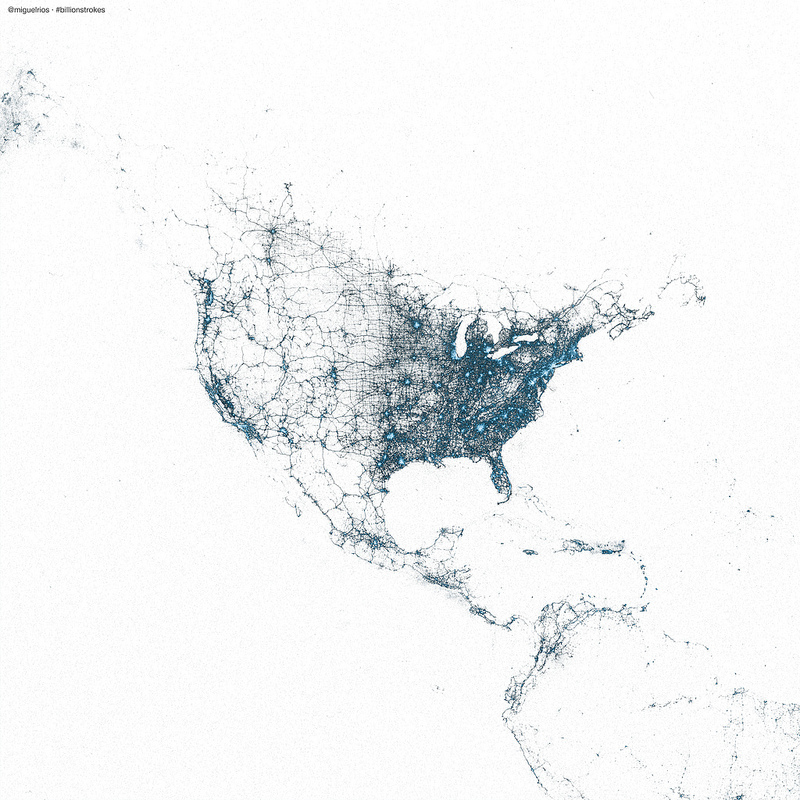

A map of the world by tweets

With geo-tagging enabled, tweets include information on the location of the user when the tweet was sent. Miguel Rios (@miguelrios) has plotted locations of billions of tweets to create maps of the world. This is pretty amazing stuff – a world map rendered just from twitter posts!

Maps are created using every tweet from 2009 using R and the ggmap package.

Post is here with more here on flickr.

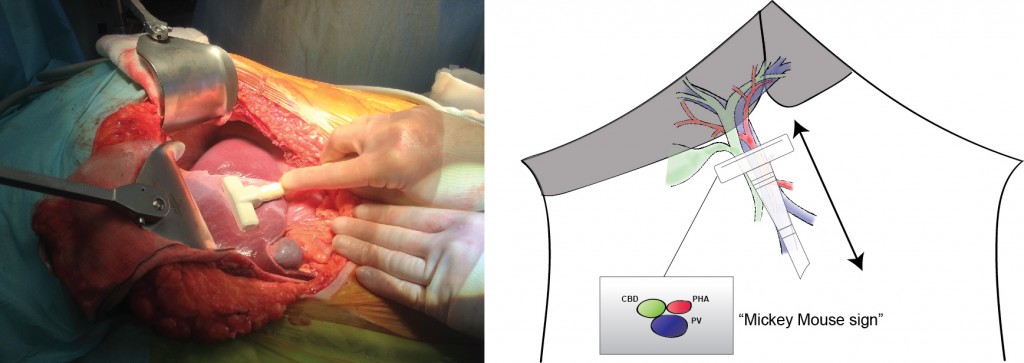

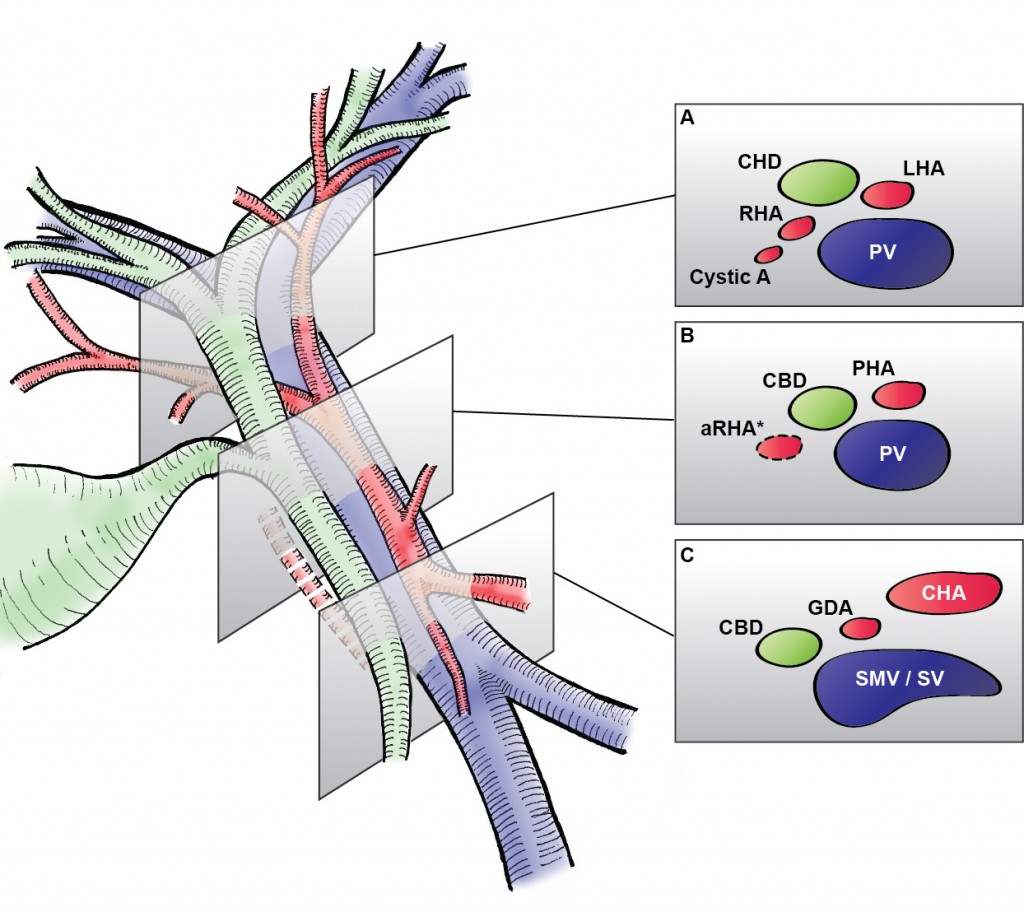

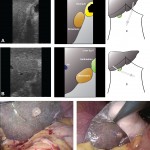

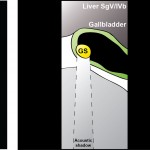

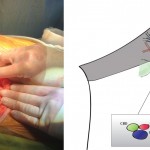

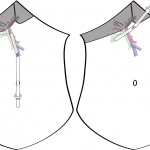

Images in operative ultrasound

Mickey Mouse and the tubes connecting the liver

In liver surgery, it’s often important to know the exact layout of the connections the liver has to the rest of the body. Here are some images which hopefully make it clear. The liver is unusual because it has two blood supplies. The first is an an artery, the hepatic artery, which carries oxygen to the liver. The other is the portal vein which carries blood from the guts to the liver and contains the nutrients from food. The portal vein carries 3 times as much blood as the artery and is not to be messed with – 34% of patients with a portal vein injury do not survive.

The other important tube is the bile duct. This drains bile from the liver to the guts. If it gets blocked – by a gallstone or cancer – the patient becomes jaundiced (the skin going yellow).

We use an ultrasound machine to visualise the vessels and the bile duct. It can be tricky and difficult to interpret. The boss has a good technique for getting orientated – the Mickey Mouse sign. When seen in the transverse plane – imagine sitting at the patient’s feet looking up through the body towards the head – the large portal vein with the artery and bile duct in front looks like Mickey. I use this technique every time.