ProPublica is an organisation performing independent, non-profit investigative journalism in the public interest. Yesterday it published an analysis of surgeon-level complications rates based on Medicare data.

Publication of individual surgeons results is well established in the UK. Transparent, easily accessible healthcare data is essential and initiatives like this are welcomed.

It is important that data are presented in a way that can be clearly understood. Communicating risk is notoriously difficult. This is particularly difficult when it is necessary to describe the precision with which a risk has been estimated.

Unfortunately that is where ProPublica have got it all wrong.

There is an inherent difficulty faced when we dealing with individual surgeon data. In order to be sure that a surgeon has a complication rate higher than average, that surgeon needs to have performed a certain number of that particular procedure. If data are only available on a small number of cases, we can’t be certain whether the surgeon’s complication rate is truly high, or just appears to be high by chance.

If you tossed a coin 10 times and it came up with 7 heads, could you say whether the coin was fair or biased? With only 10 tosses we don’t know.

Similarly, if a surgeon performs 10 operations and has 1 complication, can we sure that their true complication rate is 10%, rather than 5% or 20%? With only 10 operations we don’t know.

The presentation of the ProPublica data is really concerning. Here’s why.

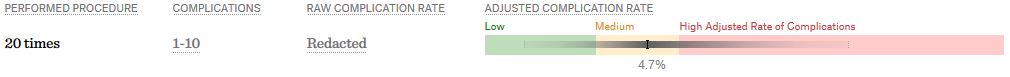

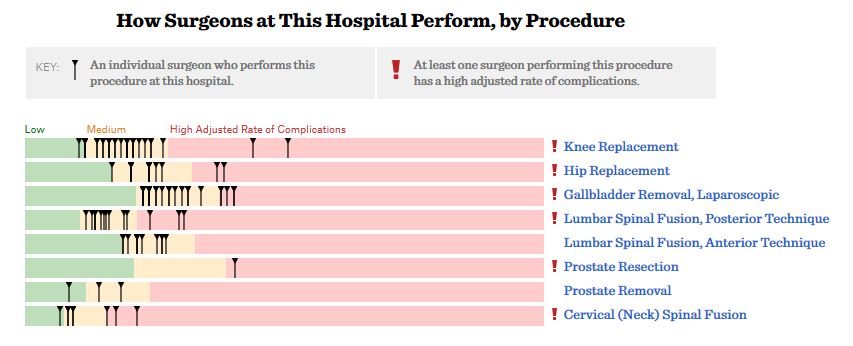

For a given hospital, data are presented for individual surgeons. Bands are provided which define “low”, “medium” and “high” adjusted complication rates. If the adjusted complication rate for an individual surgeon falls within the red-zone, they are described as having a “high adjusted rate of complications”.

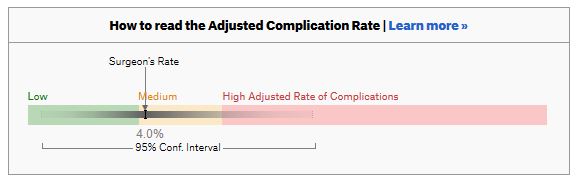

How confident can we be that a surgeon in the red-zone truly has a high complication rate? To get a handle on this, we need to turn to an off-putting statistical concept called a “confidence interval”. As it’s name implies, a confidence interval tells us what degree of confidence we can treat the estimated complication rate.

How confident can we be that a surgeon in the red-zone truly has a high complication rate? To get a handle on this, we need to turn to an off-putting statistical concept called a “confidence interval”. As it’s name implies, a confidence interval tells us what degree of confidence we can treat the estimated complication rate.

If the surgeon has done many procedures, the confidence interval will be narrow. If we only have data on a few procedures, the confidence interval will be wide.

If the surgeon has done many procedures, the confidence interval will be narrow. If we only have data on a few procedures, the confidence interval will be wide.

To be confident that a surgeon has a high complication rate, the 95% confidence interval needs to entirely lie in the red-zone.

A surgeon should be highlighted as having a high complication rate if and only if the confidence interval lies entirely in the red-zone.

Here is an example. This surgeon performs the procedure to remove the gallbladder (cholecystectomy). There are data on 20 procedures for this individual surgeon. The estimated complication rate is 4.7%. But the 95% confidence interval goes from the green-zone all the way to the red-zone. Due to the small number of procedures, all we can conclude is that this surgeon has either a low, medium, or high adjusted complication rate. Not very useful.

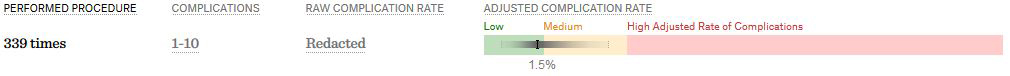

Adjusted complication rate: 1.5% on 339 procedures. Surgeon has low or medium complication rate. They are unlikely to have a high complication rate.

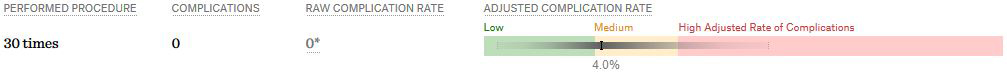

Adjusted complication rate: 4.0% on 30 procedures. Surgeon has low or medium or high complication rate. Note due to the low numbers of cases, the analysis correctly suggests an estimated complication rate, despite the fact this surgeon has not had any complications for the 30 procedures.

Adjusted complication rate: 4.0% on 30 procedures. Surgeon has low or medium or high complication rate. Note due to the low numbers of cases, the analysis correctly suggests an estimated complication rate, despite the fact this surgeon has not had any complications for the 30 procedures.

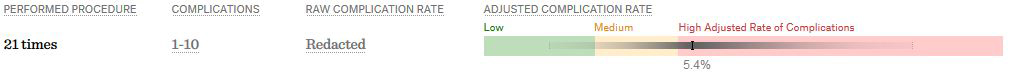

Adjusted complication rate: 5.4% on 21 procedures. ProPublica conclusion: surgeon has high adjusted complication rate. Actual conclusion: surgeon has low, medium or high complication rate.

Adjusted complication rate: 5.4% on 21 procedures. ProPublica conclusion: surgeon has high adjusted complication rate. Actual conclusion: surgeon has low, medium or high complication rate.

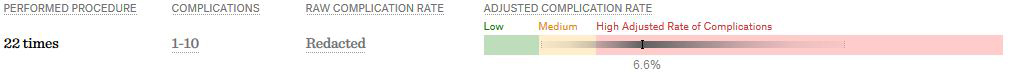

Adjusted complication rate: 6.6% on 22 procedures. ProPublica conclusion: surgeon has high adjusted complication rate. Actual conclusion: surgeon has medium or high complication rate, but is unlikely to have a low complication rate.

Adjusted complication rate: 6.6% on 22 procedures. ProPublica conclusion: surgeon has high adjusted complication rate. Actual conclusion: surgeon has medium or high complication rate, but is unlikely to have a low complication rate.

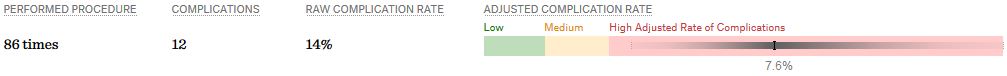

Adjusted complication rate: 7.6% on 86 procedures. ProPublica conclusion: surgeon has high adjusted complication rate. Actual conclusion: surgeon has high complication rate. This is one of the few examples in the dataset, where the analysis suggest this surgeon does have a high likelihood of having a high complication rate.

Adjusted complication rate: 7.6% on 86 procedures. ProPublica conclusion: surgeon has high adjusted complication rate. Actual conclusion: surgeon has high complication rate. This is one of the few examples in the dataset, where the analysis suggest this surgeon does have a high likelihood of having a high complication rate.

In the UK, only this last example would to highlighted as concerning. That is because we have no idea whether surgeons who happen to fall into the red-zone are truly different to average.

In the UK, only this last example would to highlighted as concerning. That is because we have no idea whether surgeons who happen to fall into the red-zone are truly different to average.

The analysis above does not deal with issues others have highlighted: that this is Medicare data only, that important data may be missing , that the adjustment for patient case mix may be inadequate, and that the complications rates seem different to what would be expected.

ProPublica have not moderated the language used in reporting these data. My view is that the data are being misrepresented.

ProPublica should highlight cases like the last mentioned above. For all the others, all that can be concluded is that there are too few cases to be able to make a judgement on whether the surgeon’s complication rate is different to average.